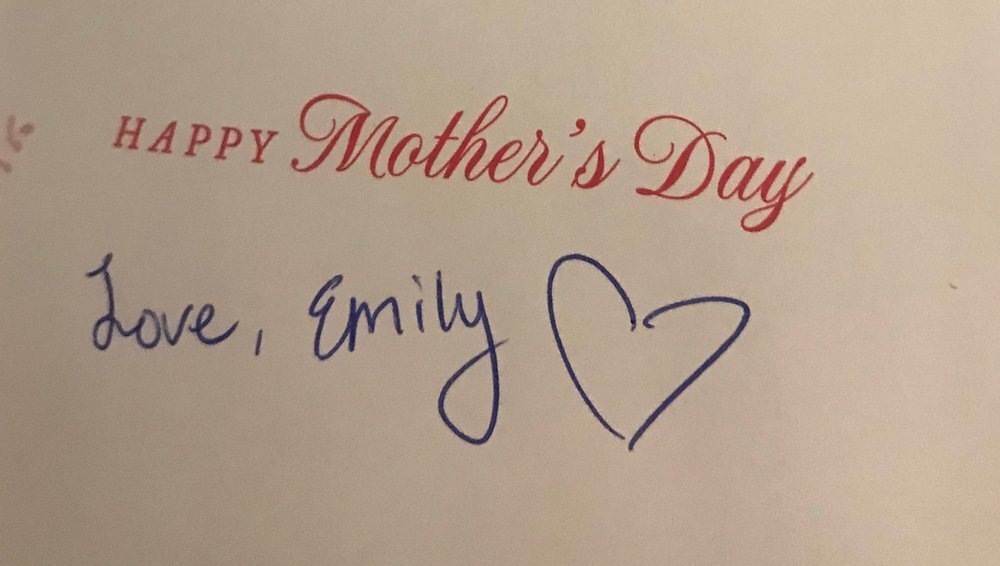

I cling tightly to the memory of the last day I saw my daughter, Emily, alive. It was Mother’s Day, May 13, 2018, just three days before she died. I’ve recounted that day in previous blogs, but I noticed that I only wrote about the happy parts–the flowers she gave me and the beautiful card with such sweet words that I will always cherish.

What I didn’t write about was her underlying irritability on that day and her anxiousness to get away from all of us. She showed up late for brunch, and I was later disappointed that following a visit with a dear family friend, who was like a grandmother to my children, Emily immediately left. Thank God she said, “I love you,” and I said it back. We have those last words to each other. But I had hoped that she would spend the entire day with me. I realize now that she probably was irritable because she needed to use, or the drugs were wearing off, and that she was anxious to get away because she needed to get high so she wouldn’t get sick.

Even admitting that my last Mother’s Day with my daughter wasn’t perfect is hard for me. We want only to remember the best of the dead. We want to gloss over the underbelly of emotions that we don’t like, or in some cases, don’t even want to admit to ourselves that we have. The truth is, I was dreading the days to come. My family was planning an intervention, hoping to get Emily to admit she had a problem and agree to go to treatment. Of course, we never got that chance. Emily died just three days before we were to carry out our plans.

Five years ago, I was full of anxiety but also full of hope on Mother’s Day. For several years following my daughter’s death, Mother’s Day seemed like an impossible task. I just wanted to run and hide from the memories of my last day with my daughter, along with those uncomfortable emotions of feeling like I must have failed as a mom for my daughter to use heroin laced with fentanyl and die. For so many of us, Mother’s Day isn’t the utopia our culture makes it out to be. Some of us have lost our children. Others are estranged from their kids. And then there are those who are missing their own mothers. Grief comes in many shapes and sizes, and Mother’s Day can be a wallop of pain for many. Society tells us to be happy on Mother’s Day. I’m here to tell you it’s okay to be sad. Forcing ourselves to act otherwise is inauthentic.

On Mother’s Day weekend, 2023, I have another daughter graduating from college. It’s a joyous time that deserves celebration. It also means I will be surrounded by all of my other children. I’ve come to realize that the anticipation and dread leading up to these anniversaries, holidays, and birthdays after a child dies is often much worse than the actual day itself. I have a game plan for this upcoming Mother’s Day. I will breathe, live in the moment, and focus on my living, now-adult children. They have now all been alive longer than Emily. They all know I love them, and I’m so proud of each of them. That hole in my heart from losing my oldest child is still there. But somehow, my heart has grown even larger to compensate for it. A mother who lost her child more than a decade before Emily once told me, “Life can be richer and more beautiful after experiencing such pain if you allow it.” She’s not wrong. I will long for Emly this Mother’s Day, and those bittersweet memories will still be with me. But I will also be grateful for the children who are still here with me and let my mother and dear aunt know how much they mean to me. Mother’s Day is both bitter and sweet, and I’m okay with that.

Faith, Hope & Courage,

Angela

Leave a Reply